Woodlands

Beth Stoddard’s Woodlands

essay from the 2022 exhibition catalogue

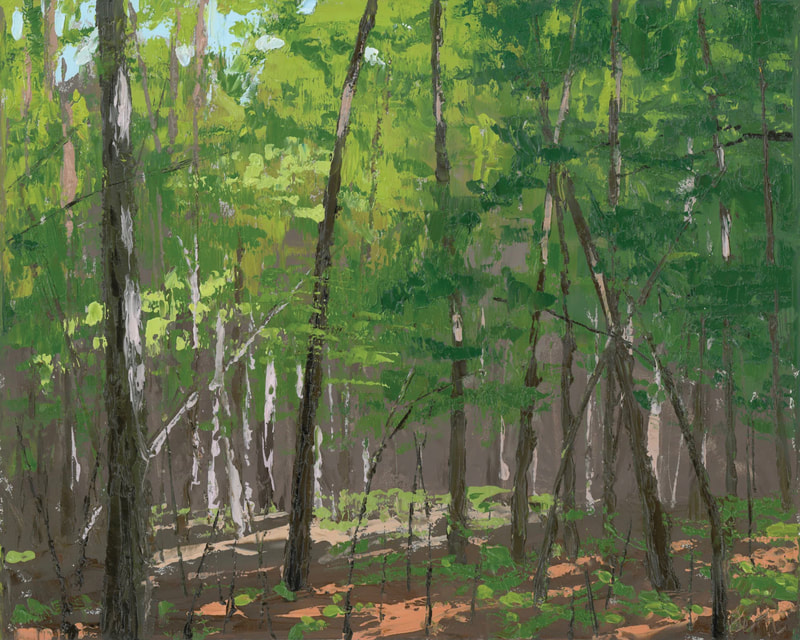

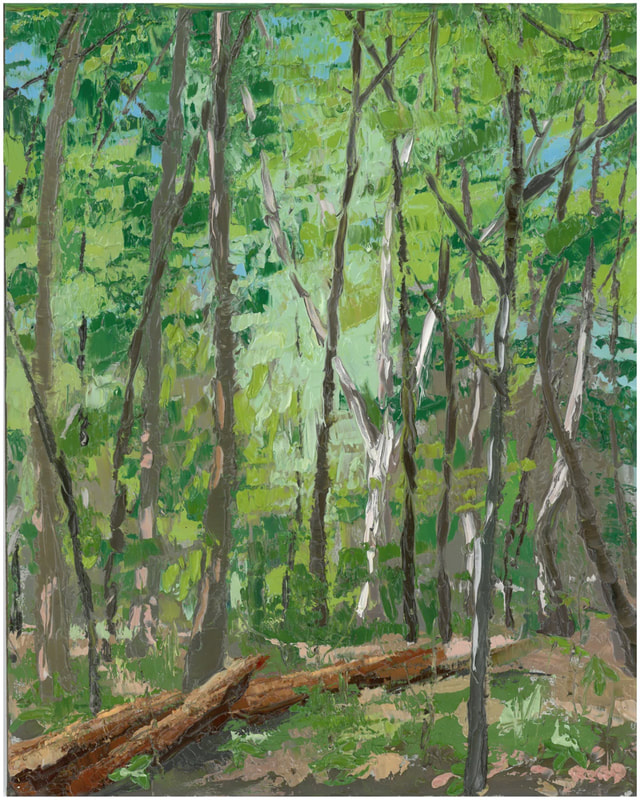

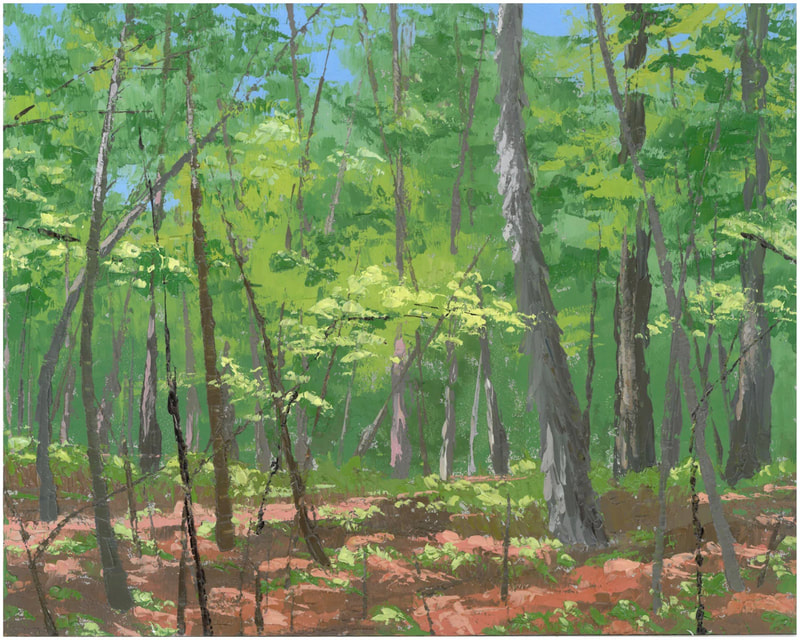

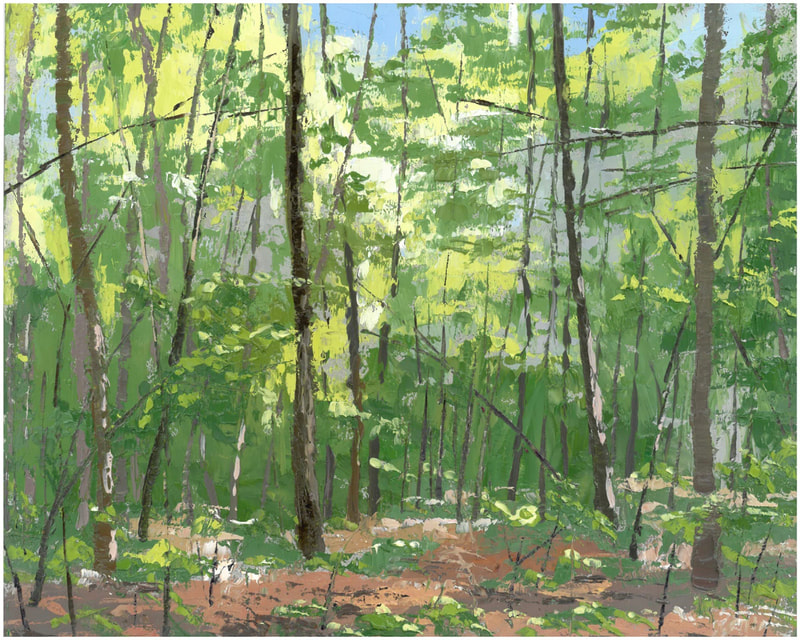

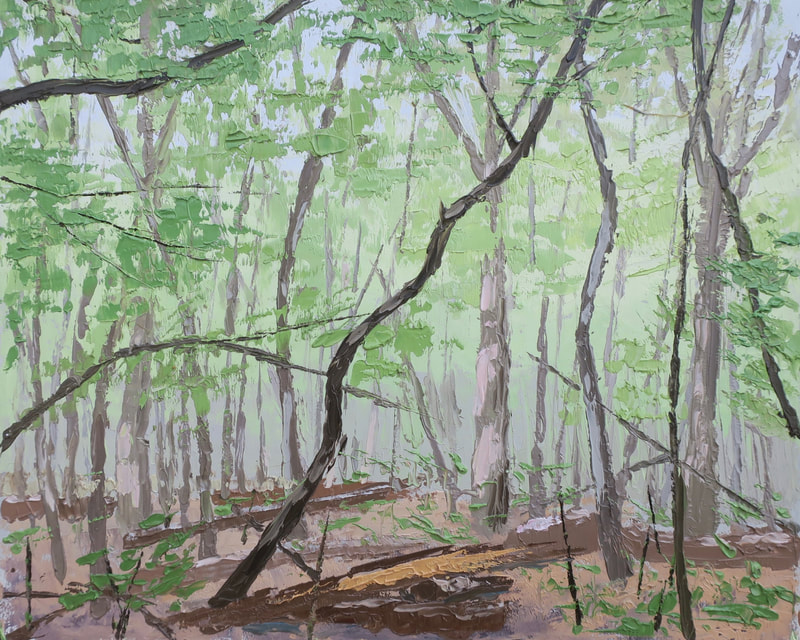

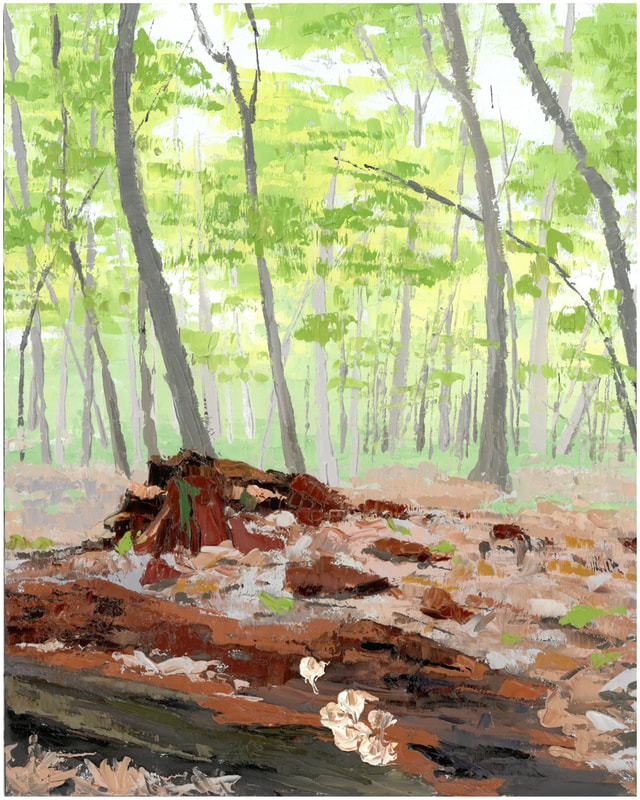

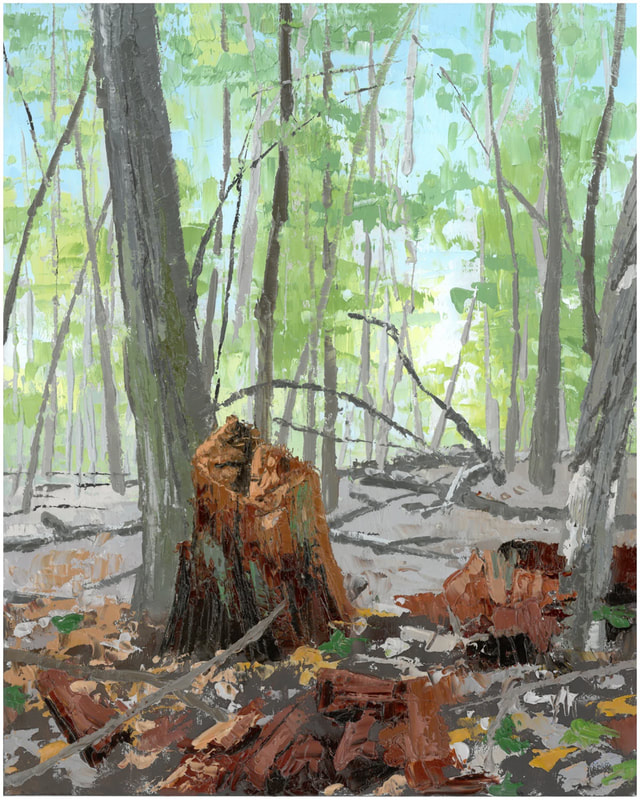

Beth Stoddard’s series of forest interiors have a devotional commitment to the experience of seeing and painting. Like a secular rosary, each painting in the series is an improvised prayer to the ever-changing beauty of the world. The shared format of the pictures and the duration of their performance, a single sitting, places an expressive emphasis on limitation itself. On an eight by ten inch board, Stoddard opens a small window on the worlds within the world of woodland space.

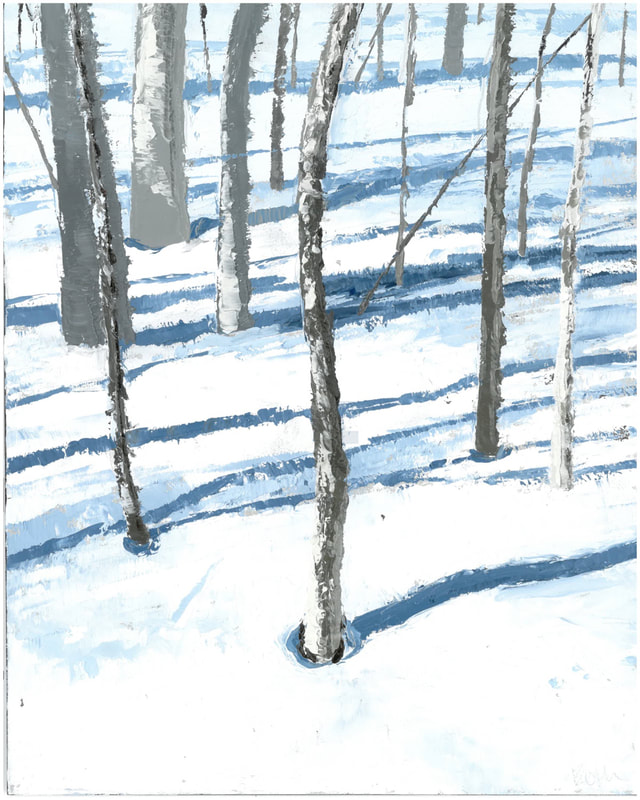

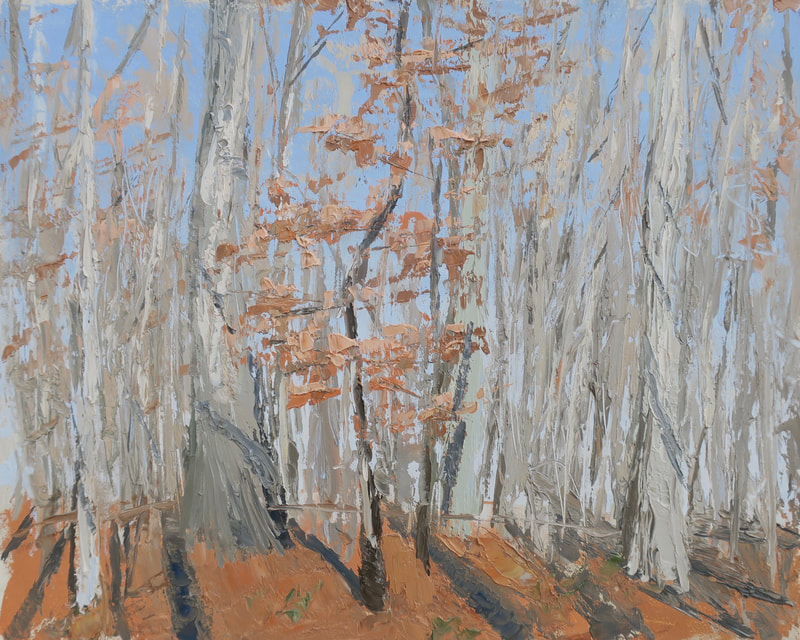

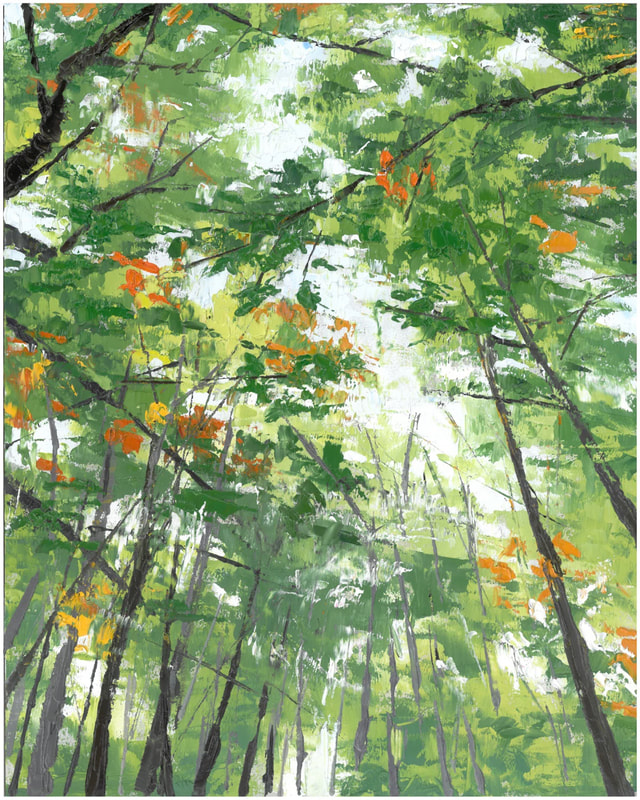

A strong picture almost effortlessly escapes to the realm of metaphor. Pigment on a surface transforms into light, atmosphere and a pageant of things arranged in depth. Stoddard’s woodlands frankly emphasize the viscous, dragged and dabbed nature of paint spread with a palette knife on a panel. An attentive viewer can almost reverse engineer the becoming of the image in the finite number of colors that express a wet day in spring and the layering of those colors to evoke trees in winter hibernation, a muddy track in the leaves or distant hikers moving through a wooded arcade. With the viewer’s complicity, the mute substance of paint magically becomes a world. Stoddard’s paintings suggest an emotional continuity between the banalities of recipe painting and the great poetic refinement of Courbet, Pissarro and Tom Thomson, all painters who share her ambition.

Human beings were painting for eons before doors and windows bloomed in their dwellings. But, when pictures became settled formats within architectural space, pictorial illusions became windows on the world. The picture as window is a particularly resonant theme in Stoddard’s paintings because her woodlands feel like interiors pierced by constellations of lighted openings, windows in the woods. The palette knife lays down patches of sky-colored paint in screens of green foliage with light entering the shaded interior as if through shutters and blinds. Reflections in streams and pools of water and ice share in the uncanny feeling of a window opening on the forest floor. The multitude of spaces between stands of trees and layers of leaves echo the gaudier, jewel-like glimpses of sky and so suggest doorways, passages and rooms until some of the paintings evoke a labyrinthine palace, a Wisconsin forest Alhambra.

Beth Stoddard’s painted world offers a prospect of a maker coming to terms with change, complexity and an almost random profusion of visual data. The painter finds a way to embrace the complexity through pattern, gesture and analogies to architectural space. The layers of painted notation, the concise palette of colors tuned to a specific day in a finite season, the feeling each mark embodies a sympathy with the gesture of the forest’s forms, all this expresses an alignment between the artist’s body and the world disclosed in painterly seeing. Are we painting the land or the land painting us?

Although Stoddard’s paintings are daily entries in this unfolding alignment and, in this sense, an offering to the viewer, a painter knows there is something withheld and, probably, unavailable to even the most passionate picture lover. Painting’s greatest gift is to the practitioner. Day after day, the practice of painting transforms the maker raising questions, and sometimes answering them, in a physical meditation on the world without and within. This last seems most important. In a paradox peculiar to painting, pictures function simultaneously as objects, windows and, disarmingly, mirrors of our nature, needs and desires. In her documentation of her woodlands project, Stoddard photographed a painting in the series with palette and pochade box nested in a bed of fallen leaves, yet another window made or opened in the flow of the seasons to hold a poem about our relationship with the world.

Scott Noel

July 2022

Philadelphia

essay from the 2022 exhibition catalogue

Beth Stoddard’s series of forest interiors have a devotional commitment to the experience of seeing and painting. Like a secular rosary, each painting in the series is an improvised prayer to the ever-changing beauty of the world. The shared format of the pictures and the duration of their performance, a single sitting, places an expressive emphasis on limitation itself. On an eight by ten inch board, Stoddard opens a small window on the worlds within the world of woodland space.

A strong picture almost effortlessly escapes to the realm of metaphor. Pigment on a surface transforms into light, atmosphere and a pageant of things arranged in depth. Stoddard’s woodlands frankly emphasize the viscous, dragged and dabbed nature of paint spread with a palette knife on a panel. An attentive viewer can almost reverse engineer the becoming of the image in the finite number of colors that express a wet day in spring and the layering of those colors to evoke trees in winter hibernation, a muddy track in the leaves or distant hikers moving through a wooded arcade. With the viewer’s complicity, the mute substance of paint magically becomes a world. Stoddard’s paintings suggest an emotional continuity between the banalities of recipe painting and the great poetic refinement of Courbet, Pissarro and Tom Thomson, all painters who share her ambition.

Human beings were painting for eons before doors and windows bloomed in their dwellings. But, when pictures became settled formats within architectural space, pictorial illusions became windows on the world. The picture as window is a particularly resonant theme in Stoddard’s paintings because her woodlands feel like interiors pierced by constellations of lighted openings, windows in the woods. The palette knife lays down patches of sky-colored paint in screens of green foliage with light entering the shaded interior as if through shutters and blinds. Reflections in streams and pools of water and ice share in the uncanny feeling of a window opening on the forest floor. The multitude of spaces between stands of trees and layers of leaves echo the gaudier, jewel-like glimpses of sky and so suggest doorways, passages and rooms until some of the paintings evoke a labyrinthine palace, a Wisconsin forest Alhambra.

Beth Stoddard’s painted world offers a prospect of a maker coming to terms with change, complexity and an almost random profusion of visual data. The painter finds a way to embrace the complexity through pattern, gesture and analogies to architectural space. The layers of painted notation, the concise palette of colors tuned to a specific day in a finite season, the feeling each mark embodies a sympathy with the gesture of the forest’s forms, all this expresses an alignment between the artist’s body and the world disclosed in painterly seeing. Are we painting the land or the land painting us?

Although Stoddard’s paintings are daily entries in this unfolding alignment and, in this sense, an offering to the viewer, a painter knows there is something withheld and, probably, unavailable to even the most passionate picture lover. Painting’s greatest gift is to the practitioner. Day after day, the practice of painting transforms the maker raising questions, and sometimes answering them, in a physical meditation on the world without and within. This last seems most important. In a paradox peculiar to painting, pictures function simultaneously as objects, windows and, disarmingly, mirrors of our nature, needs and desires. In her documentation of her woodlands project, Stoddard photographed a painting in the series with palette and pochade box nested in a bed of fallen leaves, yet another window made or opened in the flow of the seasons to hold a poem about our relationship with the world.

Scott Noel

July 2022

Philadelphia